I wanted a straightforward explanation of practice-based research – one that was clear, and that I agreed with, and which unpicked some of the complexities. So, this morning, I wrote one, in the form of a conversation with myself. Here it is.

(First published in March 2021. Revised and extended in January 2022).

In January 2022, by the way, I also wrote an even more compact and straightforward explanation, ‘Practice-based research: A simple explainer‘.

What is practice-based research?

Practice-based research is work where, in order to explore their research question, the researcher needs to make things as part of the process. The research is exploratory and is embedded in a creative practice.

What about practice-led research, research through practice, and the Canadian term ‘research creation’?

There may be subtle differences in emphasis, but these are basically all the same thing.

Can you give us some examples?

Well, for the new practice-based PhD at Ryerson FCAD we said:

Research areas within the program are diverse and may include:

→ New models of journalistic dissemination

→ Curation and contemporary exhibition practices

→ Experimental modes of storytelling and user interaction

→ Digital fashion design and fabrication

→ Creative technology development and prototyping

→ Innovation in music production and distribution

→ Numerous other areas of creative media practice

But those are areas you might work in, not examples.

Good point. A reporter from student newspaper The Ryersonian noticed the same thing, and asked me for examples of what a practice-based research student might actually do, so I said that three examples might be:

→ Exploring ways in which people with disabilities can interact with technologies to produce electronic music – through creating prototypes of those devices and working with those communities;

→ Exploring how sculpture can help people to navigate and make sense of their neighbourhoods – including making the actual sculptures and observing people’s feelings and interactions with the work;

→ Developing an idea for an online news platform which engages young people to have a voice on topical issues – by making prototypes of the platform, both as a technology and as a business model.

OK good. But this is quite normal research, though, isn’t it? Like, a scientist or engineer would explore, say, how to make a new kind of engine, by actually making that engine, wouldn’t they, and evaluating how that works. And they’re exploring how to make it work, or work better, engaged in a creative process, right? In fact the majority of research in all fields involves making something and evaluating it, doesn’t it?

Hmm yeah. Well that’s fine and good, in that it shows that “practice-based research” isn’t really an especially weird or novel invention.

So then how is practice-based research a new or novel thing at all?

Fair question. Well, we’re talking about research in the social sciences, arts and humanities specifically. In the social sciences, research was traditionally about going out and seeking to gather objective information about the lives and experiences of actual people in society. In the arts and humanities, research often meant reading books, and/or considering other people’s creative works, and developing philosophy or theory around these observations (sometimes called, a little rudely, but not too inaccurately, ‘armchair theory’). So in this context, the idea of making something is actually novel. And the idea of the researcher as a creator – beyond writing – is novel.

So practice-based research in the social sciences, arts and humanities is novel because it positions the researcher as a creator, who is engaged in an exploratory creative process in order to explore their research question.

Yes. Exactly. That’s it.

In those examples you gave to The Ryersonian, aren’t they actually all examples of interesting qualitative research, and they do happen to involve developing or making something, but then you evaluate them in the world in relation to other people’s responses. These are interesting examples of research, perhaps, but they retain traditional roots in social research, don’t they?

Hmm, fair point.

And in your own PhD, David Gauntlett, you worked with groups of young people, aged 7–12, to make videos about the environment, yeah? In order to explore how they feel about the environment and environmental issues.

Yes.

And was that practice-based research?

No, I don’t think so. It was a novel way of exploring how other people felt about a thing. It’s what we came to call ‘creative research methods’ – as in other projects, where we invited people to make drawings, or collages, or metaphorical models in LEGO – as detailed in my 2007 book Creative Explorations. But it’s not practice-based research, primarily because it involves asking participants to make the things, not the researcher themselves.

Indeed, when I was primarily a ‘creative research methods’ researcher, it was absolutely fundamental that the researcher wouldn’t do the making themselves, because that would be arrogant and put the researcher at the centre rather than putting participants at the centre. That was part of how we defined ‘creative research methods’ – that we supported participants to have their own voice, creatively expressed, and really sought to ensure that it was a deep reflection of their own feelings or experiences, not those of the researcher.

Oh! So you’re opposed to practice-based research!

No no. That was ages ago. I’ve come to embrace more the insights that come from the personal experiences of the artist-researcher themselves. And that’s just different. It’s not a superior form of sociological research – indeed, as sociological research it’s probably fair to say it’s straightforwardly worse.

But there are other kinds of knowledge. You just have to be clear about what you’re doing, and to take care not to generalize from yourself to the universe. (See this classic article, which surveyed a set of qualitative research articles – namely, every qualitative study published in the journal Sociology within one calendar year– and found that almost without exception, the authors stated that of course we cannot generalize from their data, and then went on to generalize anyway).

[For more discussion of whether what *I* do is practice-based research, see the post ‘Do *I* do practice-based research?‘, which I wrote immediately after this one].

OK. So if we go back to the three examples you gave to The Ryersonian, they do have the researcher making the things– but they also seem to rely on those things being validated by other parties afterwards.

To be honest that’s because I didn’t want my example projects to seem just purely autobiographical, or, to use the fancier term, autoethnographic.

Autoethnographic?

Yep, that’s a thing. As Haynes (2018) puts it, autoethnography is a method where “the researcher is the focus of reflexive inquiry”, but it is recognized that “the researcher’s self is inevitably experienced and positioned within a social [and cultural] context”, and so autoethnography “enables the researcher themselves to form a subject of lived inquiry within a particular social [and cultural] context”.

Oh right: autobiography.

Well, OK yes, most autobiographies are going to involve, in some way, the things mentioned in that definition of autoethnography. But autobiography is primarily about telling a story of one’s life, whereas I guess autoethnography should be more like a rather rigorous staring at one aspect of experience. So, it is different.

OK. But that definition we arrived at – “practice-based research in the social sciences, arts and humanities … positions the researcher as a creator, who is engaged in an exploratory creative process in order to explore their research question” – did sound like practice-based research can be autobiographical, or autoethnographic.

Yes, actually it can be. And that’s the purest form. It’s justifiable: you’ve explored something in very great depth, by doing it yourself very extensively, and thereby understanding it more intimately than you ever could if it was someone else doing it.

Another way of justifying it is to say, well if it’s ok to do a whole PhD about how a well-known poet used particular themes and techniques to achieve their aesthetic effects, or a whole PhD about how a well-known politician used certain styles of communication to shape their career and networks – where in both cases you’re engaging in well-informed speculation, basically, and knitting together your own opinions or interpretations and other people’s opinions or interpretations – then why would it not be OK to study your own creative processes, where at least you have a really proper knowledge of what they are, and how they felt. (You may not be an independent judge of the quality of the outputs, but that doesn’t matter).

It can’t be research if you’re just writing about yourself though, eh? That’s silly.

Well at least you have direct access to these experiences. If you’re willing to think and write about them very fully and honestly, it’s the richest form of qualitative data that you could have – that’s kinda undeniable.

And, not being funny, but everything’s relative. All research has problematic aspects. Any social science research, for instance, has the problem that when you study a sample of people, you are literally only looking at the sorts of people who would ever agree to participate in your study, which is actually a peculiar slice of people. Most of us are too busy or uninterested to bother. The people who do want to spend some of their valuable time participating in a sociology or psychology study are, empirically speaking, unusual – sorry but it’s true. So all the social science knowledge which acts like it’s based on studies of typical people is actually based on studies of non-typical people.

And even within that, the material it gathers is just what people are willing to communicate, and are able to communicate – if the research design even allows them to do so (which it often doesn’t). We don’t need to go into all the problems with all the research methods here. But suffice to say, those other methods are imperfect and partial.

If research is based on your own direct experience of creative processes, is that less reliable? It’s kinda problematic, for sure, but what isn’t. It’s not difficult to argue that it’s more reliable than the second-hand data you could get from anyone else.

Yes, OK. That makes sense.

I think for me, I do really like the idea of “the researcher as a creator, who is engaged in an exploratory creative process in order to explore their research question”, but also it does get a bit uncomfortable around that point that it’s just autobiographical. Basically, it does seem a bit odd and unconvincing to call it research if the only thing you’ve researched is yourself. But there’s ways to get away from that, and to improve the situation dramatically.

Most obviously – (1) Having arrived at some findings based on a thorough exploration and analysis of your own creative process, you can add a stage (or multiple different stages) where these findings are triangulated with the experiences of others. [Triangulation is “the practice of using multiple sources of data or multiple approaches to analyzing data to enhance the credibility of a research study” (Encyclopedia of Research Design)].

Or – (2) Your discussion of your own creative processes, experiences and findings can be embedded within a thoroughly-researched discussion of other people’s processes, experiences and findings in the same kind of area, or similar-but-different areas.

Both of these are eminently do-able and make the whole thing much more solid. So what you end up with is led by, or initiated from, the rich personal experience of a creative practice, but you’ve also contextualized it in terms of a broader set of experiences, other people’s experiences.

Yes, that makes it more sociological. But can’t we have a version which just isn’t sociological at all? Could we have a project which just digs rigorously into the process and experiences of making, of trying to fulfil some kind of idea, but without reference to what anybody else thinks, or has previously done?

This would basically work, but it needs to be clear that a research question is being pursued, as we’ve already said, and also the ‘rigour’, that you mentioned there, is key. So we would expect to see lots of stages of production and iteration and really digging into the practice, and development of ideas over time. All of this would have to be well documented.

This is what distinguishes a practice-based research project from just general creative practice that someone would do for other reasons.

Are there other things that distinguish practice-based research from other kinds of making and creativity?

Another distinction is the heavy emphasis on a process of discovery – with emphasis there on process, and on discovery – and a genuine journey, to learn something you didn’t know at the beginning.

So if someone applies for a practice-based PhD with a proposal which says ‘I intend to make this film – don’t worry, I’ve made films before – here’s the script and the budget, it will involve these locations and will be one hour long’, that doesn’t sound right at all because they are presenting a thing which appears to be 90 per cent solved already. What we are looking for is an intriguing question, and some ideas about how that question might be creatively explored. That’s where it begins, and it’s only much further into the journey that you might be thinking about some final products to display.

OK. Now, speaking of ‘final products’: in the practice-based PhD, what the student ultimately submits is not just a big long text, but actual creative work – and/or documentation of that creative work – as well as a written discussion, yes?

Yes.

So you’ve evaluating the final product? Isn’t the creative work meant to be part of the exploratory process, and so it’s not really about a final product?

Yes fair point. But what’s being submitted at the end is basically documentation of the process – actual creative evidence of the process – so that we and other people can see what the process was and how it helped you arrive at your conclusions. We’re not assessing the creative work as ‘good’ or ‘bad’ final products. That’s not what they’re there for.

Hmm. I’m sure I’ve seen PhD programs that say that the final assessed thing is a text talking about the aims of the project – the research questions – and the process, and what they arrived at, as well as the final creative work(s), which are assessed too.

Well OK. But I think these things are taken together, and there’s not some objective evaluation of the quality of the creative work (that’s not really possible, is it – quality doesn’t exist as a standalone, measurable thing) . . . but they would probably want to see that thoughtful effort had gone into making carefully produced things, as part of the process, and the seeking of answers to the research questions, which is what we’re fundamentally interested in. But obviously it’s interesting to look at the stuff that was made, as well as the writing. These things go together – you don’t really want one without the other.

Right. One last thing: since we keep mentioning PhD programs – does that mean practice-based research is something you can only do at the PhD level?

Oh no – that would be a bad misunderstanding. No, you can do practice-based research at any level, of course. Because there are now practice-based PhD programs, that’s perhaps where it necessarily gets most precisely defined. But practice-based research is an approach to research, and to knowledge, and is not to do with any qualifications in particular.

OK. Surprisingly this has all turned out to sound very reasonable.

Hurray!

After I wrote this, I wanted to work out whether what *I* do is practice-based research, so I wrote the post: ‘Do *I* do practice-based research?’.

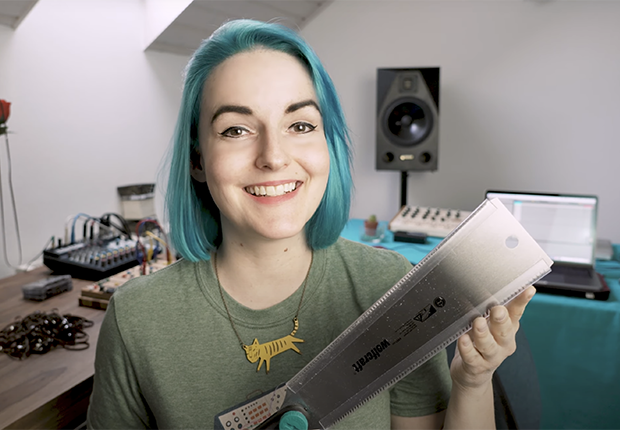

The top image is from PanicGirl’s video, ‘Cutting Tape Loops – With a Saw‘. If that’s not practice-based research, I don’t know what is.

Fantastic entry! Thank you!

So completely helpful and understandable. Thankyou

I’ve started an MA in fine Art and am exploring the notion of practice led research.