In the first half of 2017 I am writing the Second Edition of my book Making is Connecting. It has been nice to reaquaint myself, if I may say so, with lots of bits in the first edition of the book that I had basically forgotten.

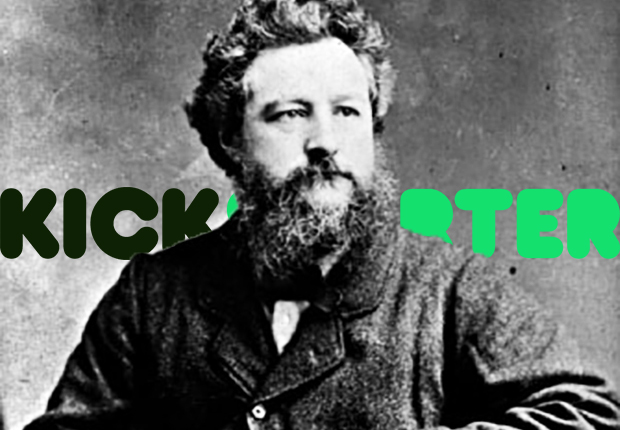

In particular, in this blog post I want to share with you this part about William Morris, who is an incredibly inspirational figure for makers.

William Morris (1834-96) shared the views of John Ruskin (1819-1900) about the vital importance of creativity and self-expression in society, but he took the argument further by means of actually making things.

The rest of this post is basically a chunk from the book. Near the end I link up William Morris with what people do on Kickstarter, and with LEGO – those are new bits for the Second Edition – which is the kind of connecting between the past and the present that I like to do in Making is Connecting. So here we go.

Morris the maker

John Ruskin suggested that individual self-expression is so vital that if a society creates supposedly rational systems which do not allow a voice to people’s individual creativity, then the whole system rapidly becomes sick and degraded, like a tree in barren soil.

William Morris believed this passionately, and developed this emphasis on individual creative expression into a more expansive vision of happy, empowered creative communities. As Viscount Snowden put it in 1934:

He aimed at a community of fellowship in which all individuals would share in common the joys of creative art.

Morris had been embroiled in medieval fantasies and Romantic literature from an early age. He had read Walter Scott’s historical novels before he was seven, played games of knights, barons, and fairies, and visited old churches with his father. But as he became a young man, medievalism took on a more developed meaning, in tandem with new research which was building knowledge about medieval life. As his excellent biographer E. P. Thompson puts it:

For Morris, the most important result of the new scholarship was in the reconstruction of a picture of the Middle Ages, neither as a grotesque nor as a faery world, but as a real community of human beings – an organic pre-capitalist community with values and an art of its own, sharply contrasted with those of Victorian England.

Although life in Medieval England had its share of difficulties and injustices, it was not systematically engineered to degrade the human spirit, or wedded to the notion of self-interest as the inevitable motive of all behaviour. Being able to evoke a clear picture of a way of living so very different to his current reality helped Morris to retain his genuine faith in the possibility of change.

And whilst Ruskin was something of an amateur artist as well as art critic, Morris combined theory and practice much more comprehensively. He mastered all kinds of creative techniques during the course of his lifetime, moving on from painting and drawing to embrace embroidery, woodcuts, calligraphy and book printing, tapestry weaving, and textile printing. He clearly felt that a hands-on engagement with a craft was the only way to truly understand it.

Morris decried the ‘profit-grinding society’ with its abysmal working conditions and ‘shoddy’ goods. Like Ruskin, he felt that workers should be able to take pleasure from making beautiful things from the finest materials. Unlike Ruskin, though, Morris was a well-organised entrepreneur and avid multi-tasker, who didn’t waste any time in creating a successful business in response to this need. Thus, in 1861, Morris, Marshall, Faulkner & Co. was founded – ‘Fine Art Workmen in Painting, Carving, Furniture and the Metals’ – producing handcrafted objects, wallpaper and textiles for the home, as well as major commissions for the decoration of rooms at St. James’s Palace, and the South Kensington Museum (now the V&A), as well as several churches. In 1875, the business came under Morris’s sole ownership, as Morris & Co.

Later in life, in 1891, Morris also founded the Kelmscott Press, which used the approach and printing techniques of 400 years earlier in order – as Morris explained to a journalist in 1895 – to give ‘a beautiful form’ to ‘the ideas we cherish’. By this point Morris’s craft work had become more of an all-consuming hobby than a commercial venture, and the Press only issued limited numbers of its expensively-made volumes.

‘Time-travellers from the future’

Morris’s dedication to the production of high-priced luxury objects, and the lavishly decorated Kelmscott Press books, can seem puzzling since their very high production costs meant they were necessarily only available to an elite. In an 1891 newspaper interview, Morris presented his vision of a socialist society where ‘We should have a library on every street corner, where everybody should read all the best books, printed in the best and most beautiful type’. But in his own time, Morris did not seek to begin a ‘books for all’ publishing revolution, as Allen Lane would do later with affordable Penguin paperbacks. Instead he made exclusive hand-crafted treasures.

A helpful explanation for this anomaly is offered by Tony Pinkney:

From this standpoint, then, the Kelmscott Press books, however expensive and restricted in social circulation in their own day, are not evidences of medievalist nostalgia and political withdrawal, but are rather time-travellers from some far future we can barely imagine, showing how lovingly artefacts might be crafted in the socialist world that is to come.

Although Morris did not articulate it quite in this manner, this seems an appropriate way of understanding what his high-class business was really meant to represent. Morris’s battle was fought on two fronts: first, to prompt a transformation of society, via grand and revolutionary plans, this necessarily having to happen at a point in the future; but second, to modify and disrupt things, in the here and now, by inserting finely-produced material objects, and ethical working practices, into a society accustomed to ‘shoddy’ products and exploitative factories.

Clive Wilmer, editor of the very good Penguin Classics selection of Morris’s work, News from Nowhere and Other Writings, similarly defends the author by explaining, on his behalf, that ‘the creation of beautiful furnishings and so on is part of a process of public education, providing a model of good production methods and pioneering a return to higher standards of design’. The expensive Kelmscott Press books are therefore consistent with Morris’s ‘all-or-nothing politics’ – he would rather show the world the true ideal book, rather than compromise with more affordable models of lower quality.

Once we see Morris’s craft work in this light, we can see that his written works – poetry, fiction, and prose – are just other dimensions of the same project. So rather than thinking that William Morris was a man who ran a craft business, and who also happened to be a writer of poetry and novels, and who also found time to produce political critiques and pamphlets, we instead come to the realisation that William Morris was a man who projected a vision – a vision of great fundamental hope and optimism – through a striking number of different channels. On the one hand it might be a utopian novel, such as News from Nowhere, which fast-forwards the reader to an ideal, pastoral world of the future, where Morris would like you to live, or on the other hand it might be a utopian sitting-room, which fast-forwards its inhabitant to a world of well-made, comfortable and attractive domestic objects, which Morris would like you to live in. Along with the political non-fiction writings, they are all ‘visionary accounts of an ideal world’, as Wilmer puts it, reminding us of the possibility of alternatives: ‘To dream of the impossible and disregard reality is to question the inevitability of existing circumstances’.

Today, that spirit is perhaps seen in the higher-quality, carefully-made, and relatively more expensive products offered at craft and maker fairs, and online stores, where people who have produced lovely garments and finely-packaged vinyl records have the courage to ask a necessarily higher price for them – because quality and hard work cannot be cheap, but they do command respect. We might think, too, of the crowdfunding site Kickstarter, where ‘investors’ are invited to buy into the desire of a creative person to make something, and to follow them on the journey. Ultimately, they do typically receive a thing, but the process highlights the journey of design, creation and production, and is the opposite of the standard online-shopping mission to get things very fast and very cheap.

And I do, actually, count LEGO in here – they are a hugely successful multi-national company, of course, and LEGO is perceived as a relatively expensive toy. But in all my dealings with the company over many years, I have only seen a huge commitment to quality and creativity in play, and giving people the best quality experience with a creative product, responsibly and ethically produced. Of course, being so big means the company has a lot of power, and there have been missteps along the way: LEGO’s relationship with gender issues, for instance, has been tricky, although not always bad. Seeing LEGO products as Morris-like ‘visionary accounts of an ideal world’ might seem a bit far-fetched, but I do think they are trying, and that has great value.

Head, Heart & Hands matter most, ‘all prototypes begin with the hand’ (as stated by Dr. Stephen Green, Imperial College London (via Co-Innovate Brunel, 2015)).