A year ago, I wanted to work through a sort of definition of practice-based research for myself, and so I wrote a piece called ‘What is practice-based research?’, which was literally just for myself, and took the form of a conversation with myself about it. And then it seemed good enough to put here on this blog.

It’s imperfect, though. It takes a rather circuitous route to its conclusions, via this conceit of being a discussion with myself about it, and even includes mentions of things I’ve done myself. And immediately after that, I was fascinated to explore ‘Do *I* do practice-based research?’ – which is indeed fascinating, if you’re me. But most of you are not me.

So here’s a new attempt to write a straightforward one-page explanation.

Practice-based research

Practice-based researchers explore their research questions through practice. They have to make things and experiment, and that is a necessary and essential part of the research process. They couldn’t do their research without doing this hands-on creative work.

Because making stuff is something that lots of people do, and is not usually called ‘research’, we might wonder what exactly it is that makes it research in these cases.

This is actually quite straightforward to answer if we revert to the apparently even more broad and challenging question of ‘What is research?’.

A neat answer to that question was decided by the architects of the UK’s research assessment exercise, currently called the ‘Research Excellence Framework’ (REF), a massive bureaucratic undertaking that aims to evaluate all the research undertaken by academics at UK universities.

Everybody hates the REF. But at least it forced people to talk about what research is, and even more startling questions, like what is it for, and does it make a difference to anything. And so they were compelled to come up with a definition of research that would work across all disciplines, from physics to history, ceramics to mathematics, poetry to zoology, and all points in between.

And so they decided that research is: ‘a process of investigation, leading to new insights, that are effectively shared’. This is beautiful. It is very straightforward and also very flexible.

So what is practice-based research? It is just that. It is a process of investigation, leading to new insights, that are effectively shared.

And that’s it. The definition is perfect for a creative practice-based approach to research, since it requires that we develop the process of investigation, and arrive at new insights, and effectively communicate these things, but doesn’t specify anything about what those might look like, or how you would do them, or where you would put them.

And nobody can question it because it’s literally exactly the same words as the most fundamental definition of all research, as defined by one of the world’s most punishing arbiters of research standards.

Incidentally, you may ask, how does the REF process know if all this research is any good. Well, again with stunning simplicity, everything – no matter what its form or discipline – is scored in terms of three things, ‘originality’, ‘significance’ and ‘rigour’. (For a bit more info, you might like to see this one-page PDF from the REF2021 website).

You only need to think about it for one second to realize that there are ghastly problems to do with who judges these things, and the ways in which academics police their disciplines and suppress outsiders and oppose innovation. We might each have very different ideas of what is ‘originality’, and what is ‘significance’ and what is ‘rigour’. But as a basic aspiration – as a thing to aim for, based on your own understanding of these terms, at least – it’s pretty clear.

Obviously, we are not just talking about the UK’s REF exercise here, we’re talking about the core components of successful practice-based research in general.

Like all research done in a university, practice-based research needs to ultimately be of value for some people or communities beyond just the person doing the research. That’s where the ‘originality’ and in particular the ‘significance’ come into play. Exploring a creative technique just so you get better at doing that creative technique, for instance, is not enough, unless it also brings valuable and unexpected findings – one way or another – that are useful for others.

This route to usefulness doesn’t have to be entirely direct. That’s why the ‘one way or another’ clause, just there, was important. Each bit of practice doesn’t have to lead to a message that will be instantly embraced as a searing insight by everybody, as long as cumulatively these practice-driven explorations add up to something.

Here you can find a few more things on this site about practice-based research.

If you want to read something more substantial, my friend Sunil Manghani published an article a couple of months ago, with the deceptively modest title ‘Practice PhD toolkit‘. It’s actually a wonderful introduction to all the rich philosophical questions about what a kind of research based in practice could mean.

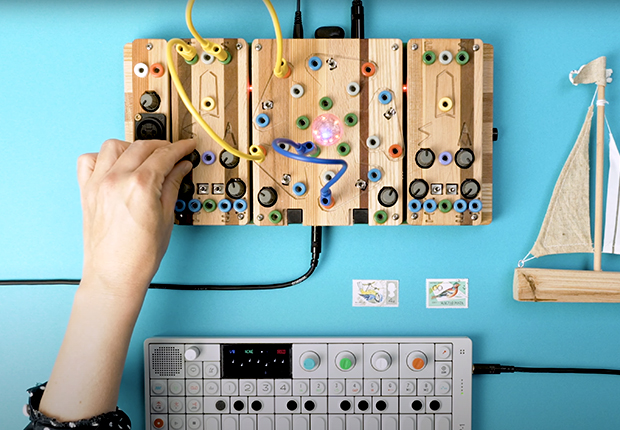

Since my previous post on this topic featured an image from PanicGirl’s video, ‘Cutting Tape Loops – With a Saw‘, this one continues the theme with a still from her video, ‘OP-1 and Cocoquantus Jam‘.

Leave a Reply