I really enjoy making music. I’m not especially good at it, in a musical sense. But I love sounds and tinkering with them, and I love getting insights about the creative process from something that’s different to other things. (I mean, for example, it’s quite a lot different to making visual things, which sit there right in front of you and all at once).

Since we moved to Canada in February 2018, I hadn’t felt able to make any music. Everything was so new and gently overwhelming, and I didn’t really have the head-space to do it. So music-making became dormant for 20 months.

But then in October 2019, after I’d asked Camille Favreau if she’d like to produce the Creativity Everything podcast, she then asked me if I could do a bit of music for it. This was a reasonable request and a good idea, but I left embarrassed that I’d lost the ability to do music, and made an excuse that I was too busy and wouldn’t be able to.

But then, over the next few days, I realized to myself, oh come on, you’ve got to rise to this challenge and get making music again.

So I accepted the challenge to make a little 15-second thing, and once I’d started, I realized that I’d stumbled into a mirror of one of my favourite Brian Eno stories, where he accepted a Microsoft commission to write the opening-up music for Windows 95, which was required to be “optimistic, futuristic, sentimental” and various other adjectives, and be 3.2 seconds long. Eno had been creatively stuck, but the experience of trying to make such a small but meaningful thing – “like making a tiny little jewel” – meant that afterwards, when he went back to making three-minute songs, it seemed like “oceans of time”.

In terms of becoming unstuck, I’d had the same experience.

And then I spent many hours working on a piece of music that was always less than half a minute long, and by the end I rather liked the idea that I’d spent more than 30 hours on a thing that lasted less than 30 seconds.

Anyway the other key striking thing was about feedback.

My typical experience of feedback, I guess, is when you’ve finished something and then a grumpy academic reviewer says they don’t like it, and they say you should have done it how they would have done it instead. I don’t enjoy that feedback at all, and, moreover, I’ve almost never found that useful. (Sorry, grumpy academics!)

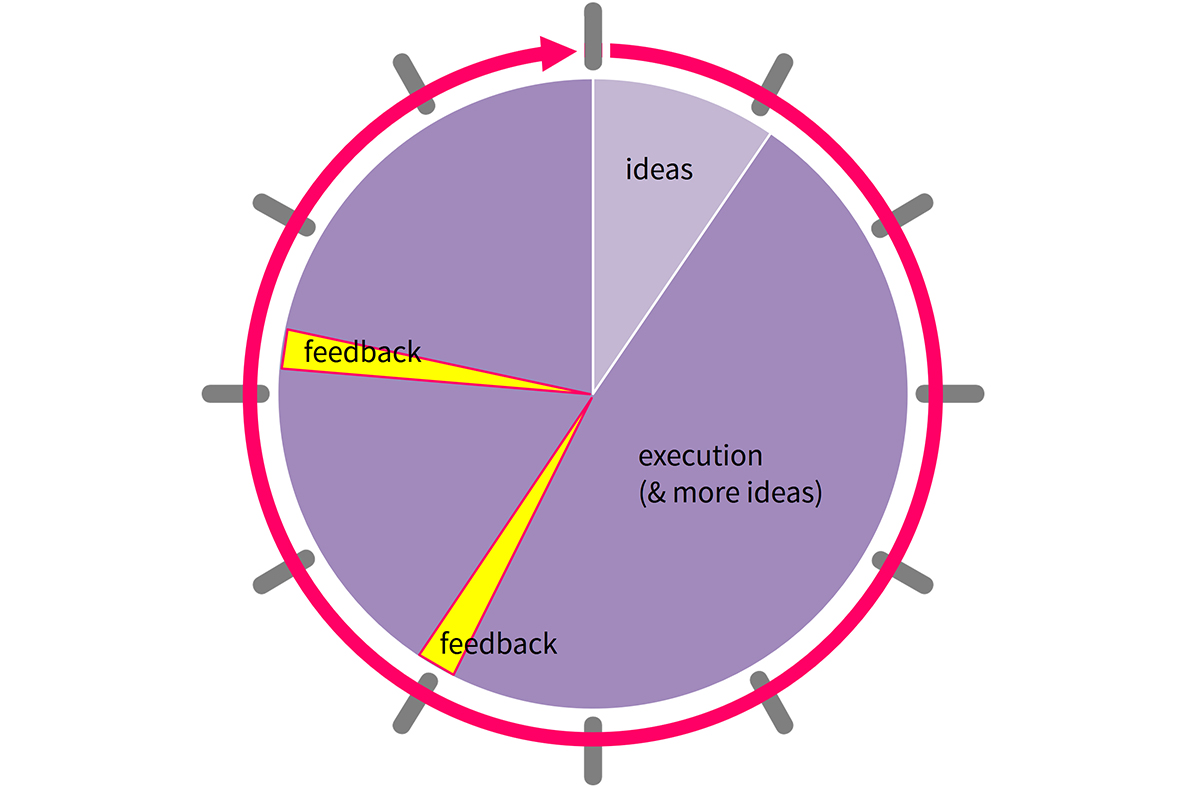

But, this was quite different. What happened here was … er, we’re going to need a diagram.

[ * draws diagram * ]

Right, so in this diagram . . .

. . . you can see there’s the first bit (starting at top-of-the-clock position in the 30+ hours-long process of making this piece) which is just trying out a few ideas and not really settling on anything, and then quickly – probably too quickly – moving into making something out of an early idea and then spending lots more time adding things and (less often) taking things away, and manipulating and changing things, but basically going forwards and forwards and forwards on the long march to try to make it better.

But, in the yellow shards, I asked one key trusted and intelligent person – that’s my wife Jenny, who would probably say that she knows very little about music, but she’s clever and sensitive and thoughtful and honest, which is what counts – for any words of feedback.

And what she provided me with, each time, were just little thoughts and phrases that made a big difference. For example, she said it sounded like I was “in a hurry”, which was very striking. And she said maybe it could be more “playful”, and again, this was very interesting. These little things – I guess it’s like when actors get “notes” from a director – were ever so useful and led to actual changes in the finished thing.

They were sufficiently vague that I didn’t feel like I was being told what to do, and equally, that I didn’t need to generate a defensive explanation of why I had or hadn’t done something. They were hints and suggestions, which was perfect.

If I’m saying that getting feedback from other people can be useful, I suppose that’s not a very original point. This is a little more refined: I’m saying that at certain key moments in the creative process, I invited a trusted person to give me a few pointer words and phrases, and that really helped with thinking about the work and shifting direction a bit, to make it better. I don’t really get feedback like that normally. It was really good.

So, my recommendation is this: don’t wait until you’ve finished something and then ask for feedback. It’s too late by then, and the feedback will merely be upsetting.

And, don’t get feedback constantly throughout, because it’s too much and doesn’t give you the chance to breathe and be yourself.

Instead, ask one or two trusted people for a few reflections and pointers only – just a few words or phrases, really – and you will experience these as glittering shards of super usefulness in the creative process.

Yes! We have to have the courage to start it spinning, but then, once we are moving, nudges are so important. Only with feedback, we have to ask for it and want it.