| From the archives, this post is from May 2011 (the original, with some comments, is here). It originally had the longer title, ‘”Making is Connecting” on Thinking Allowed: What the listeners said – including my dad’. By May 2013 I had pretty much forgotten about this post, and so was pleased and touched (all over again) to see my dad writing in to stick up for me! |

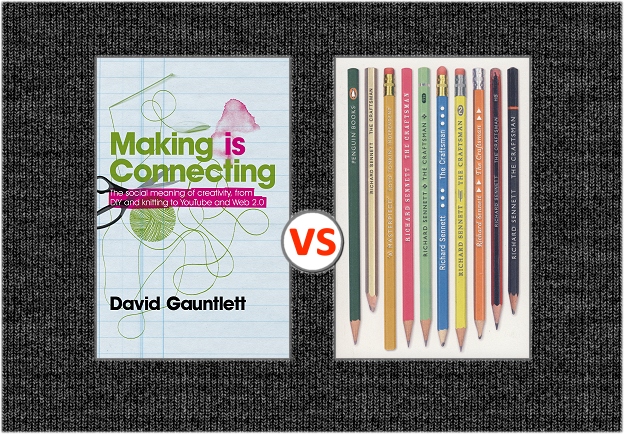

A couple of weeks ago I was on ‘Thinking Allowed’, the BBC Radio 4 (also BBC World Service) discussion programme presented by Laurie Taylor. The subject was my new book ‘Making is Connecting: The social meaning of creativity, from DIY and knitting to YouTube and Web 2.0’, and I was very happy to be joined by Richard Sennett, the former LSE professor who wrote the excellent book, ‘The Craftsman’ (2008).

You can listen to or download the MP3 podcast of the programme via this page (scroll to ‘Craft and Community’, 27 April 2011), or see the website of the book which includes videos, events, and extracts.

Richard Sennett was very nice, and supportive, in person, but when the microphones were turned on he took on a more combative edge, which made for, I hope, a lively discussion.

I did not anticipate that our differences would be very substantial, but Sennett seemed to argue that people do not do craft and making activities because it gives them feelings of pleasure and pride – rather, he emphasised the pain and struggle, and the time it takes to master a craft.

This stems, I suppose, from our different approaches to craft. I’m interested in what I call ‘everyday creativity’: activities by anyone where they make and share things – online or offline – because they want to. Whereas Sennett seemed to be thinking of the more professional or virtuoso type of ‘craftsmanship’.

In the contexts I’m talking about – people making YouTube videos, blogs, music, knitting, craft projects or fun robots – it doesn’t really make any sense to say that people don’t enjoy what they do, for the straightforward reason that if they didn’t like it they simply wouldn’t bother doing it.

He also said that people had not yet done very imaginative things online – a point which I should have argued with more forcefully, but we were running out of time.

In any case, I thought the discussion went okay, although we didn’t seem to cover very much ground.

Unsurprisingly, the programme was listened to by a few people I know, plus some people I half-know from Twitter, and around 1.5 million others. Also listening in were my parents.

I hadn’t really thought about it in advance, but of course my dad had a particular interest in the subject, having been a woodwork teacher (later ‘craft, design, technology’) at a state school for almost all of his working life. It’s nice to have your dad on your side, obviously, and in this case I was very pleased that he turned out to be, in our weekly phone call, both irritated and indignant about Sennett’s argument.

I asked him to write it down for the sake of this blog post, and this is what he sent:

In his opening comments, David defined one of the contributors to happiness as having the opportunity to express oneself through making, and being able to see a project through from inception to fruition. Also there is happiness and satisfaction in creating.

Children get immense satisfaction and happiness from the process of creating with their hands and the sense of achievement with the finished object, however modest. For some pupils who fail in most academic subjects, to find opportunities for self-expression and satisfaction, craftwork is their best chance of achieving satisfaction and ‘joy’ (to use that contentious expression) in learning.

I take issue with Richard Sennett’s view that the only joy comes, or should come, with the final achievement of near perfection. He said more or less that commitment and keeping going were what mattered, and if you aim to get pleasure from the making process then the first time you come to a difficulty ‘you have a problem’. This sentence in itself does not make sense; of course a difficulty is a problem. However if you have enjoyed the making process you will have gained knowledge and confidence to tackle the difficulty, as well as joy from the process of small achievements along the way.

When we say ‘making is connecting’ we should not be thinking of thousands of hours to achieve top craftsmanship, but the joy of small successes, and satisfaction in modest achievements.

The programme led me to think about the reasons why adults came to craft evening classes. Some came for social contact, others just to use the equipment and facilities. Others pursued a particular interest (such as a dentist who renovated old furniture), or to learn to use tools and create. But all felt the need to express themselves in a craft. Local authorities have killed off most of these opportunities by insisting only on courses that lead to NVQs [National Vocational Qualifications] or some other piece of paper. School craft and design seem to ‘dabble’ instead of giving real opportunities for achievement. And so other outlets have been sought, privately funded art or craft groups for example. Perhaps the internet may provide new opportunities, and new awareness.

So I liked that response, unsurprisingly. I was also sent, by the producer of the radio programme, this interesting email from a listener, Cally Booker (who has subsequently given permission for it to be reproduced here). I didn’t previously know Cally – she is not even a distant relative. This is the email she sent to the programme:

From: Cally Booker

Sent: 04 May 2011 17:27

To: Thinking Allowed

Subject: online craft communitiesDear Laurie

I have just been catching up with some podcasts and have been belatedly listening to your Thinking Allowed episode on crafts and community. I’m motivated to write to you because I wanted to support David Gauntlett’s optimism regarding online craft communities.

My own craft discipline is weaving. It is by no means as mainstream (or portable) an activity as knitting and so my ‘local’ community is somewhat limited. However, weavers have been networking online for many years. There are groups varying from simple email lists, through Yahoo! groups, to specially designed weaving sites such as Weavolution. Similarly, online resources range from historic weaving drafts to YouTube demonstration videos to downloadable and print-on-demand monographs. The UK Association of Guilds of Weavers, Spinners & Dyers includes a guild which was founded nine years ago and operates entirely online. Many weavers maintain their own blogs as well as using Twitter, Facebook etc. etc.

Personally I like the blogs best. I have been maintaining my own for the last four years and think of it as my home space. When I visit other weavers’ blogs it is like popping in for a cup of tea while they show me round their studio or hold up their latest piece of work. I often get to see a little bit of their private life as well – how much is entirely up to the blogger, so (probably unsurprisingly, though maybe there is some research to be done there) the blogs I read the most are the ones where the privacy values are most similar to my own. When we meet in online groups it is more like a guild meeting: more focused on a common task or interest. Using Twitter is more like being at an enormous party, where loads of topics are thrown in the air all at once.

However, the main point I wanted to make was this: the thing I especially value about this community is that there are participants at every level of skill and experience. From my position ‘somewhere in the middle’ I can find advice from expert practitioners and offer a helping hand to beginners. I can rejoice at weaver A’s work being selected for a prestigious show and at weaver B’s completion of her first solo project. I can also talk frankly with people who are at a similar point to me in their weaving lives – an enormous benefit which is just not available to me offline because the pool of local weavers is not large enough.

Thank you for another interesting programme.

Kind regards

Cally Booker

So of course I was pleased with that feedback too. These two ‘reviews’ of our radio discussion, from Cally and from my dad, are centred on handmade crafts – with, in Cally’s case, an emphasis on how the Web can connect practitioners and amplify their collective creative efforts. In the book I also look at research studies of people who make and share things online, as well as those who enjoy real-world making and crafts, and draw together some shared themes. In fact, we find they have much in common:

* Making in itself offers pleasure, thought and reflection, and helps to cultivate a sense of the self as an active, creative agent.

* People spend time creating things because they want to feel alive in the world; to be an active participant in dialogues and communities.

* Individuals also like to be recognised within a community of interesting (like-minded) people.

Overall the book argues that creative activity is not just ‘a nice thing’ for the individual, but is absolutely crucial for a healthy and thriving society. A society which does not offer citizens opportunities to express themselves and make their mark is like a tree cut off from its roots; with no nutrients it soon becomes dull and fails. We also, of course, need to foster the creative capacity of society in order to deal with climate change and adapting to a world beyond oil, amongst other huge challenges.

Leave a Reply