A couple of days ago I caught up with Ken Robinson’s new (May 2013) TED talk, ‘How to escape education’s death valley’. As in other Ken Robinson TED talks, he wanders into his subject in a laid-back, jokey style, making important points but not apparently with great urgency, but before the end, having got your attention, he delivers a devastating and no-jokes powerful message about what we need to do to save ourselves from the disaster of our current education systems.

In this one, he arrives at a story about flowers surprisingly blooming in Death Valley, which gets us to this point:

With organic systems, if the conditions are right, life is inevitable. It happens all the time. You take an area, a school, a district, you change the conditions, give people a different sense of possibility, a different set of expectations, a broader range of opportunities, you cherish and value the relationships between teachers and learners, you offer people the discretion to be creative and to innovate in what they do, and schools that were once bereft spring to life.

Great leaders know that. The real role of leadership in education – and I think it’s true at the national level, the state level, at the school level – is not and should not be command and control. The real role of leadership is climate control, creating a climate of possibility. And if you do that, people will rise to it and achieve things that you completely did not anticipate, and couldn’t have expected.

He says another good bit, and then it’s finished. I really liked all of this, but the bit that I cut out and posted on Twitter was: ‘If you do that, people will rise to it and achieve things that you completely did not anticipate, and couldn’t have expected’.

I picked that bit because I really love the idea of a system that supports or encourages things to happen that you couldn’t predict but which are great. And maybe you knew it would lead to great things but you didn’t know, and couldn’t know, what those might be. (I can be seen enthusing about that kind of idea, for instance, in the first 30 seconds of this video filmed at the LEGO Idea House in March 2013).

It’s rather like John Naughton’s description of the internet as ‘a global machine for springing surprises’ (in this article and elsewhere). The architects of the internet, and later the Web, created a situation where people could exchange ideas and information freely and with ‘no questions asked’. They didn’t know what things would emerge from this system, but they may have had a hunch that some of those things would be incredible, and they were right.

It’s also rather like the idea of the computer as a generative system, as in Jonathan Zittrain’s nostalgia for computers that you had to program before they would do anything. This is covered in my book Making is Connecting, where on page 177 I follow Zittrain’s example of the 1977 Apple II computer:

The Apple II, as the immediate product of guys who loved to hack and tinker with technology, was a machine which, like many early home computers, didn’t ‘do’ anything when you switched it on, but waited for you to do something with it. Modern users might find this weird and unhelpful, but the positive view is that the creators of the system didn’t mind what you did with it. You could do whatever you wanted (with the necessary skills – and within the limits of possibility). This consequently meant that sales of Apple II took off for reasons which Jobs and Wozniak had no control over and were not necessarily even aware of. For instance, it was only when Apple sought to investigate why sales of the Apple II had taken a sudden upward swing that they discovered that business people were buying the machine just so that they could use Visicalc, which was the first ever spreadsheet program. Like most Apple II software, Visicalc was created by an external developer, and when Apple executives happened to have seen an early version, they had not recognised it as anything very special. But of course, they were later very happy when it helped to boost sales of their machine. Although they had not planned Visicalc itself, they had planned the unpredictable possibility of its existence.

It’s funny to look back on this now – I remember writing it in a small bedroom in Dorset when we were staying for a month with my parents-in-law because we had sold one home but not managed to acquire its replacement just yet – because it’s this idea, about unpredictable but wonderful disruptions, which arise because of some carefully arranged conditions even though the thing itself is wholly unforeseen, which I’ve been fascinated by for a long time, but without exactly realising it.

I suppose, for instance, thinking about it, it’s also the underlying theme of my inaugural lecture from 2008, where I say, if you want me to tell you the solution to global problems, I can’t tell you the solution to global problems, but what I can tell you is that we need to set up a context where people are much more routinely creative, are much more likely to play, make and exchange ideas together, and are not afraid of failure, and want to have a go.

And in more straightforward and pragmatic terms, it’s a reason why I’m a fan of LEGO, a system which gives you the tools to create wonderful things, and the LEGO company has no idea what you’re going to make, but they do know that you can do it.

It also explains what I’ve been looking for, I suppose, in the books about systems that I’ve been reading recently. (A good starter one is Systems Thinkers by Magnus Ramage and Karen Shipp, 2009). The best kinds of systems are the ones that set up supportive, creative kinds of environments, and so create the possibility of brilliant surprises.

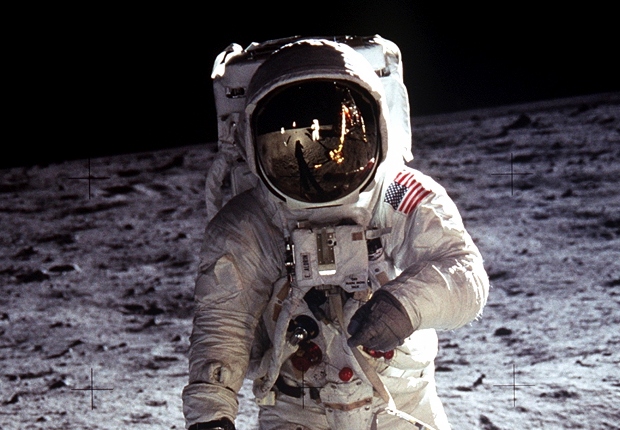

One more thing that it reminds me of is the creative ambition in the goal, announced by US President John F. Kennedy in May 1961, ‘of landing a man on the moon and returning him safely to the Earth’, and to do so ‘before this decade is out’. It could be said that this is not like setting up the possibility of unexpected outcomes – the outcome is highly specific. But they had no idea how they were going to do it. This was underlined in a JFK speech the following year, where he memorably explained: ‘We choose to go to the moon. We choose to go to the moon in this decade, and do the other things, not because they are easy, but because they are hard‘.

In this excellent speech, on a sweltering hot day at the stadium of Rice University, on 12 September 1962, he told an audience of 35,000 people:

But if I were to say, my fellow citizens, that we shall send to the moon, 240,000 miles away from the control station in Houston, a giant rocket more than 300 feet tall, the length of this football field, made of new metal alloys, some of which have not yet been invented; capable of standing heat and stresses several times more than have ever been experienced; fitted together with a precision better than the finest watch; carrying all the equipment needed for propulsion, guidance, control, communications, food and survival; on an untried mission, to an unknown celestial body, and then return it safely to earth; re-entering the atmosphere at speeds of over 25,000 miles per hour, causing heat about half that of the temperature of the sun – almost as hot as it is here today – and do all this, and do it right, and do it first before this decade is out – then we must be bold.

This captures some, but not all, of the risk involved in this incredibly ambitious plan to do something which was quite unlike anything that had ever been attempted before – involving a whole range of vehicles, systems, and equipment which simply did not exist and had not yet been invented. And to do it safely, when going into space, and over to the moon, and down onto the moon, and back up again, and then back to Earth, and then landing, involves an incredibly long list of points at which a small error would kill the astronauts, either immediately, or by leaving them stranded or shooting off into the darkness beyond their target, rather less swiftly.

The 1960s moon mission was immensely ambitious, and is a classic example of throwing a lot of money and a lot of creative people at a problem – as well, of course, as some highly structured plans and milestones – and hoping it’ll work. I still think it’s absolutely incredible that it did. In terms of this blog post, the US government set up a system within which they trusted that creativity would flourish. There’s an awful lot of trust in there: the international reputation of the United States was resting on a seemingly impossible promise, made in 1961, that they would do something unprecedently amazing before the end of 1969. To say that people rose to the challenge is rather an understatement.

And so we’re back to that key thing that Ken Robinson said: ‘creating a climate of possibility: and if you do that, people will rise to it and achieve things that you completely did not anticipate, and couldn’t have expected’.

Leave a Reply